The production of Collyweston stone slate has been taking place in the village of Collyweston for approximately 400 years. The slate is unique to the area and is of significant importance to the character of many local and national buildings, extending its furthest reach when shipped to roof Old Westbury Gardens, Long Island, New York.

Collyweston stone slate roofs are one of the most distinctive and familiar features of the historic towns and villages around the village of Collyweston in Northamptonshire, which gives its name to the stone from which they are made.

Way back, stone from the area was used as a roofing material by the Romans. Evidence has been found at several archaeological sites, where slates were found shaped roughly into diamond shapes, with a single peg hole at the top point. It is thought that earlier buildings would have been too flimsy in construction to support the weight of a stone roof.

Production of Collyweston peaked in the late 1800s, but had practically stopped altogether by the 1970s when it became commercially unviable. The chronic lack of a supply of new slates had a number of knock-on effects, which combined with the ready availability and price of modern mass-produced roofing materials, made the prospects for Collyweston roofed buildings look bleak.

Those owners who wished to use genuine Collyweston to repair their roof had little alternative but to use slates reclaimed from other historic buildings. This was hardly a sustainable supply as every replacement slate had to be taken off a historic roof elsewhere. Reclaimed slates became so lucrative, that many farmers and others were paid by contractors to strip Collyweston roofs and replace them with corrugated iron, modern tiles, or artificial products or imported materials, which were out of character.

Way back, stone from the area was used as a roofing material by the Romans. Evidence has been found at several archaeological sites, where slates were found shaped roughly into diamond shapes, with a single peg hole at the top point. It is thought that earlier buildings would have been too flimsy in construction to support the weight of a stone roof.

Production of Collyweston peaked in the late 1800s, but had practically stopped altogether by the 1970s when it became commercially unviable. The chronic lack of a supply of new slates had a number of knock-on effects, which combined with the ready availability and price of modern mass-produced roofing materials, made the prospects for Collyweston roofed buildings look bleak.

Those owners who wished to use genuine Collyweston to repair their roof had little alternative but to use slates reclaimed from other historic buildings. This was hardly a sustainable supply as every replacement slate had to be taken off a historic roof elsewhere. Reclaimed slates became so lucrative, that many farmers and others were paid by contractors to strip Collyweston roofs and replace them with corrugated iron, modern tiles, or artificial products or imported materials, which were out of character.

Whilst the Collyweston stone slate industry has never been large, specialist Collyweston stone slaters have continued to maintain the traditions and the high levels of skills required to keep remaining roofs in sound repair, however the future is now looking brighter for new roofs.

Back in 2012, the team here at Messenger were employed by English Heritage to carry out trials and further investigation into the production of new Collyweston stone slates. The aim of the trials was to replicate the natural process of splitting or ‘cracking’ the stone blocks or ‘log’, which would naturally occur when the log was exposed to frost during the winter months. Traditionally, the stone would be taken directly from the quarry, laid out in a field and regularly dampened to aid the natural freeze/thaw splitting process.

To take control over the process and replicate the natural splitting action at will, the trials centred around the use of a large freezer unit.

English Heritage purchased 80 tonnes of Collyweston log from a local quarry, this was then transported to Apethorpe Hall (now Apethorpe Palace) and laid out in readiness for the trials.

During the trial period many different sizes of log were used. These ranged from large blocks requiring mechanical help to move and handle them, down to small more manageable blocks of 150 – 200mm in thickness. The log was placed onto a pallet and wrapped in a polythene bag. This stopped the log from drying out too quickly and prevented moisture escaping into the freezer chamber. During the trials, the best results were obtained using smaller sections of the log.

Having prepared the log, it was transported on pallets to the freezer unit and placed into the chamber. Various freeze/thaw cycles were trialled with the core temperature of the stone being carefully monitored at all times. This process was carefully supervised by Dr Jefferson and staff from Sheffield Hallam University. When a successful cycle was established, the log was then removed from the freezer unit and prepared for the splitting or ‘cliving’ process by hand.

Once the frosting process highlighted the natural bedding planes within the stone, splitting of the log could be completed. This task, undertaken by hand is referred to as ‘cliving’. The individual slates are then ready for dressing to shape and size. Dependent upon the size and natural quality of the stone it was sometimes necessary to repeat the freezing process to ensure the log had reached the right stage for cliving. Once clived, the stones are then dressed to form slates, drilled ready for fixing and grouped according to their length. This process is known as ‘parting’.

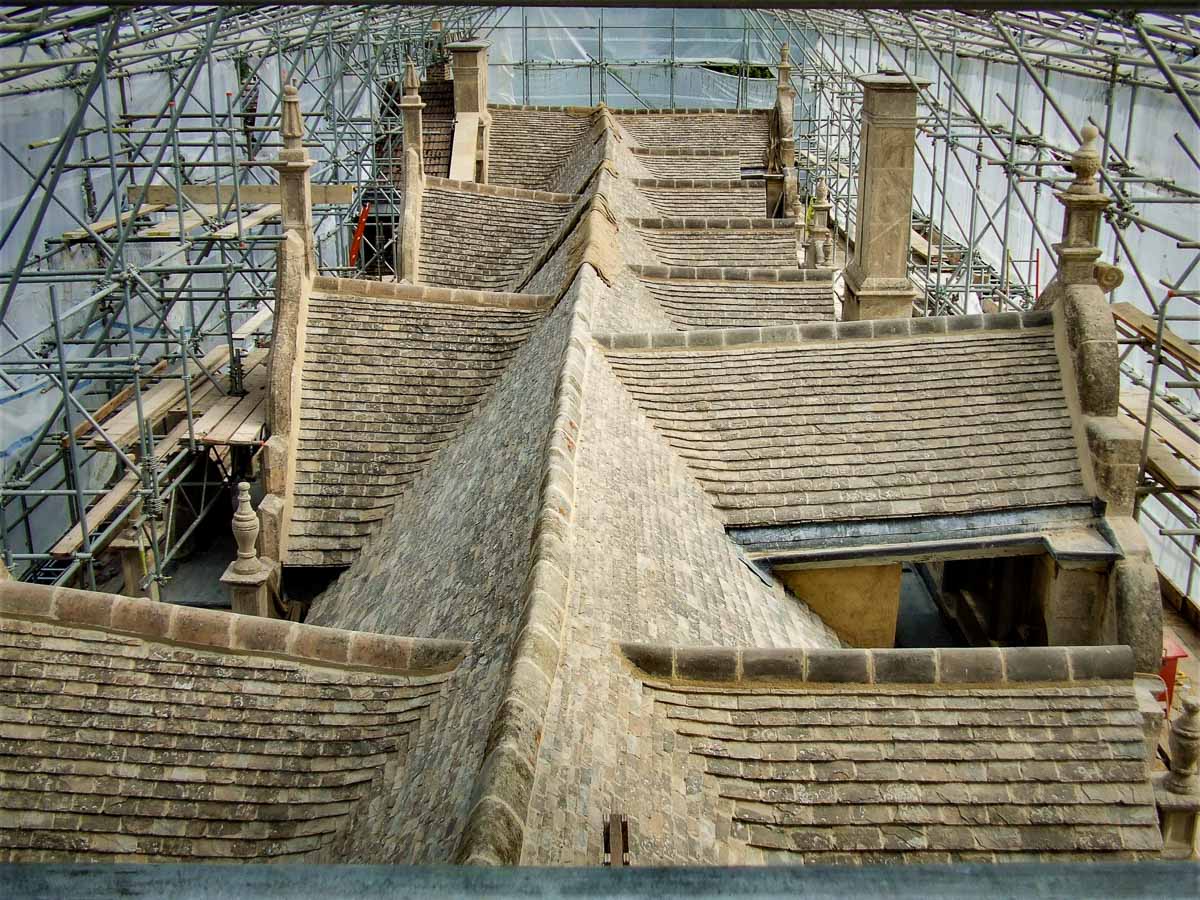

The trials proved very successful and ‘new’ Collyweston stone slate was produced and fixed to two roof slopes at Apethorpe Hall in Northamptonshire. The total area of the slopes roofed with the new material at Apethorpe was 96m2.

We continue our small-scale production and have further replaced the roof coverings at High Wycombe Town Hall with approximately 135m2 of new slate and also an elevation of the roof at St Andrew’s, Ufford in Lincolnshire. Most recently, when contracted to build a spectacular new theatre for Nevill Holt Opera, we were able to use their new handmade stone slates to supplement the re-claimed material when replacing the roof to the stable building.

Given our interest in Collyweston stone slate and the art of heritage roofing, we have dedicated space for a purpose-built exhibition and demonstration area in our newly built Head Office in the village of Collyweston. This room is roofed in our ‘new’ handmade stone slate.

We are fervently keen to ensure that the history of Collyweston stone slate, and the methods of extraction and historic production are not lost to future generations. With this in mind, Summer 2020 will see the opening of our dedicated Collyweston stone slate exhibition (visitors by appointment). In addition to providing a permanent exhibition area, the aim is to provide education and development days to interested individuals, groups, societies and school children. This facility will provide a permanent home for important archives, including written records, tools and photographs. Aside from this, we have also had a virtual reality experience produced of the former slate mine which spreads under their site, as well as engaging a local author Joshua Parfitt to collate a fascinating support booklet, encompassing a collection of tales and facts about Collyweston stone slate and some of the characters from its past and present. This is due to be published in line with the opening.